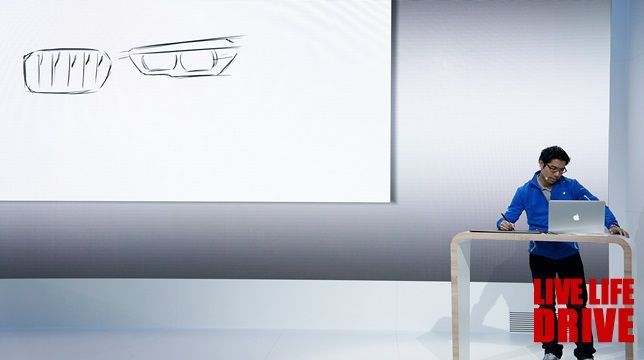

Interview With Calvin Luk, Exterior Designer For BMW 1-Series LCI and All-New X1

Live Life DriveWhat were you doing when you were 10 years old? Watching David Hasselhoff’s talking Pontiac Trans Am reversing out of speeding trailers, doodling M.A.S.K’s flying Chevrolet Camaro with guns pointing out, or rolling Matchbox cars enacting Takumi Fujiwara’s duels on the mountains of Akina?

For the then-10 years old Australian-born Calvin Luk, he was busy sketching BMW cars. Unlike many Asian parents, the Hong Kong-born Mr. and Mrs. Luk didn’t stop their young son Calvin from ‘wasting time’ drawing cars, or told him that drawing is a waste of time and that he should instead study science and mathematics, so he could pursue a typical degree in law, accounting, engineering or medicine in one of the Ivy League schools.

Twenty years of sketching and persistence later, Calvin is now one of youngest Exterior Designers at the BMW Group, responsible for the 1-Series LCI and the all-new X1.

Looking at the gleam in his eyes when talking about his work at BMW, Calvin is certainly very satisfied with his job. Definitely far more satisfied than if his parents had forced him to pursue a conventional professional degree.

His journey to pursue his dream with BMW and how he managed to secure a scholarship to study in the prestigious Art College of Design in Pasadena, California – the MIT and Harvard of automotive design - is an inspiration to any budding car enthusiast looking to pursue a career in automotive design.

Genius Is Overrated - It’s Persistence and Good Mentoring That Matters

In 1993, Swedish psychologist K. Anders Ericsson published his research paper titled “The Role of Deliberate Practice in the Acquisition of Expert Performance” in the journal Psychological Review. It argued against traditional believes that geniuses are born. Instead, Ericsson's research convinced him that not only genuises are not born, but genius is the result of continuous practice under a good mentor.

Ericsson quantified the threshold for one to become an expert is 10,000 hours of practice – 20 hours every week, for 10 years. Ericsson’s work laid in obscurity within the walls of academia for over a decade before Malcom Gladwell pushed this theory into popular consciousness when he promoted the so-called ’10,000 hours rule’ in his book ‘Outliers.’

Gladwell cited examples of Mozart, The Beatles, Bill Gates, and several top-class athletes, all whom had good talent but they were certainly not the prodigy that people later assumed them to be.

The 10,000 hours theory attracted a lot of controversy within academic circles, but many of the counter-arguments ignored the fact that both Gladwell and Ericsson advocated not just 10,000 hours of deliberate practice, but also practicing under the guidance of a mentor (else taxi drivers would’ve been top-class racing drivers).

Back to Calvin, whether he knew it or not, his path to BMW fitted Ericsson’s and Gladwell’s description of a young prodigy in making.

He started sketching cars from a very young age, and continued doing so weeks after weeks. By 16, he already had a wide portfolio of design work compiled into a book. Later on, his persistence put him in touch with a senior designer at BMW, who soon became Calvin’s mentor, guiding his work and told him that he needs to find a way to California to study in Pasadena.

Opportunity Favours The Prepared, Don’t Be Shy To Ask

Later I asked the guy at the stand if he was from Germany, because I could hear his accent. He said he was from Munich. I asked if he would be kind enough to pass on a letter for me to the Head of Design at BMW at that time, Chris Bangle.

Recalling the beginnings of his interest in cars, Calvin, who turns 30 this year said “I have always been interested in cars and when my parents bought a 3-series, an E36. I loved it so much. I kept drawing and drawing it and I knew I wanted to become a designer for BMW.”

“I was 10, and I thought that car was so cool,” said Calvin of his parents’ E36.

Throughout his teens, Calvin continued to sketch cars, honing his artistic skills and reading up everything he could about cars. By 16, he had already completed a wide range of sketches of cars, compiled into a portfolio like a serious designer, ever ready to be presented to anyone who cared.

“I was in high school when they had the Sydney Motor Show and someone from the (BMW) headquarters was in the stand. Together with my friends, I asked if we could fit as many people as we could into the back of the MINI and take a photo. We squeezed about five of us in there and took a photo. Later I asked the guy at the stand if he was from Germany, because I could hear his accent. He said he was from Munich. I asked if he would be kind enough to pass on a letter for me to the Head of Design at BMW at that time, Chris Bangle.”

To his surprise, the guy at the stand obliged, prompting the young Calvin to literally run home and typed his letter, asking Bangle how he could get a job at BMW.

“It was a letter that I wanted to write for a long time but I never knew how I could send this. And then I met this really nice guy at BMW, he is still at the headquarters office today. I ran home because I live not far away from the expo centre, typed it all out really quick and attached them with my sketches.”

Calvin’s letter did not reach his idol Chris Bangle, but he did get a reply from David Carp, who was then a Senior Designer at BMW (currently at Rolls-Royce Motor Cars).

“He recommend that I pursue my studies in Pasadena because a lot of car designers graduate from there.”

Many the best car designers – BMW’s Chris Bangle, Aston Martin’s Henrik Fisker, Ford’s J. Mays, Tesla’s Franz von Holzhausen, GM’s Larry Shinoda and Ferrari’s Frank Stephenson – graduated from Pasadena’s Art College of Design.

The entry requirements into Pasadena is extremely difficult. Every year, budding car designers from all over the world vye for a place there.

When asked about what it takes to secure a place in Pasadena, Calvin said “You have to prepare a portfolio, with a lot of your sketches. Thanks to the mentorship of David Carp, who gave me a lot of feedback on my sketches, I was able to improve my portfolio. I looked up to a lot of references from sketches at the time – the BMW X Coupe Concept for example, and sketches from Christopher Chapman (E53 X5) were really inspiring to me. I tried with Photoshop, tried with markers, and just kept trying. I put my sketches together into a book and sent it over. Thankfully they offered me a scholarship because it’s a very expensive school to attend. You also need to write a letter and answer one question, which changes every time and I can’t remember what it was. That was how I applied,” said Calvin.

From A Sketch To A Production Car

Prior to this, Calvin had already worked on several design projects for BMW but the 1-Series LCI was his first production car project, and the F48 X1 was his first project for an all-new model.

Calvin says it takes about two to three years to translate a sketch into reality. “It takes a bit of time to develop them into a three-dimensional model on a computer, and then it goes to the clay phase where we work with a team of sculptors who will build a full size (clay) model, before going into the technical feasibility stage – making sure all the technical bits are working well, the aerodynamics are good, and the stamping is good and everything works perfectly.

When asked about the 1-Series LCI, specifically about when a new design (LCI) team takes over from the launch model team, Calvin explains that there is no one particular milestone to mark the handover as each project is fluid and treated differently.

“It’s treated as a separate project, and the whole background to the project is always changing so it becomes its own project really,” he explained.

Compared to the frumpy looking launch-model 1-Series, the updated 1-Series LCI that Calvin penned looks much better. When asked about idea behind the new design, Calvin said “There were many things that were cool about it (launch model 1-Series). It was a very fresh design but it’s just that we had a lot of new technologies coming in. As soon as you have a new technology like the new light module, the new engine’s requirements. It changes the whole project. You have to change the front, the rear, so we took advantage of this and made a new car.”

The major challenge for every car designer is maintaining the harmony between the design team and the engineering team. A design that looks good on a clay model might turn out to be very difficult, or very expensive to produce on a large scale.

Complex surfaces on the body for example, can be difficult to produce as production engineers will have to ensure the steel sheet is able to withstand the bending and twisting of the steel press without tearing, all while keeping the cost manageable.

Designers might want a flushed body, low and swooping front-end but engineers need a high hood height to meet pedestrian crash safety regulations, while powertrain engineers want as much air as possible for the engine’s breathing, and to accommodate all the required components under the hood.

The tension between design and engineering is a characteristic of every car project and is something that both teams have to learn to compromise.

When asked about how he manages the tension, Calvin laughed, telling me that I have prodded a sensitive area for designers. “Oh that’s a good question. It’s always a balance. I think responsible design at BMW, we take into account the Freude am Fahren – Sheer Driving Pleasure. That means good technical and also ease of use as well. So good design is really a holistic approach and must account for the technical and also look good. If it just does one or the other then it does not take care of the entire product.”

Some designers opined that it is more difficult to design a small car (like the 1-Series) than a big car, as small cars lack the necessary length, depth and width to express a designer’s intention. However Calvin doesn’t see it that way.

“They’re just different. Different scale, obviously. They are just different projects really, different feeling.”

You Won’t Know The Final Result Until You've Started It

Unlike other designers who look to certain sculptures or works of art for inspiration, Calvin is a free-spirited designer who looks to anything and everything for inspiration.

“For me in terms of the process (for inspiration or ideas), I think of it like playing music, like in a jazz group. If you play jazz, often you don’t know how the final song is going to sound like. It just starts to happen. One person plays one thing and you start to react. You know that it works because you have the confidence that the creativity will work itself out. Design is sort of like that. You don’t know the final result before you start it, obviously. As you go you develop it, one step leads to another, and leads to another and leads to another and then you have the final picture. You bring new ideas into the song and make current ideas stronger and it’s always a balance of how you play these two elements,” said the former drummer of a jazz group.

Calvin also plays piano but does not quite like the more structured manner of playing piano, as compared to drums.

“You won’t know the final result until you've started it” – Calvin’s approach to every design is also mirrored in the way he pursues his dreams. Had he not been bold enough to walk up to the BMW guy at the Sydney Motor Show, he probably would not be have gotten his dream job.

Advice For Aspiring Designers

Calvin’s message to aspiring designers who want to pursue a career in the automotive industry is that they must be passionate about their job.

“It starts with your passion for cars. Obviously if you are not interested, then it’s probably the wrong career.

“I know a lot of people, including myself, they just love sketching. Car designers start from a very strong base on 2-dimensional sketches. I think maybe in some other fields of industrial design they get very early into 3-dimensional computer modelling but car design is very emotional. That’s why the sketching is very important because it comes from your hand. To sketch out the lines to express the surfaces, through the shading and to really create a character is a very special thing.

“So for aspiring designers, it is important to sketch a lot and just to be interested in cars, to study things you like about cars, and to be generally interested in artistic sculpture and creativity.”

At the end of this, what struck me was the approach that BMW takes in nurturing young talent.

Calvin’s personal journey with BMW shows the other side of BMW. We all know that BMW is extremely good at marketing, and knows how to stoke our desires for stylish, high performance cars.

What is less said however, is that BMW is a company that genuinely values young talent and the same attitude can be seen in their staffs, as shown by David Carp's personal mentorship of the young Calvin, to actively nurture young talent on their own initiative.

There are not a lot of brands out there that can tell such a compelling story – of sowing dreams to a 10-year old fan of the brand, giving him positive influences, providing him direction and a purpose throughout his teenage years, motivating him through his adulthood before granting him an opportunity to show his talents to wow the next generation of BMW fans. Now that’s a genuine brand story that no amount of marketing spending can craft.

Read more about the BMW 1-Series LCI and the all-new X1 at our sister-site Carlist.my:

BMW M135i - Final Call To Own A Future Classic?

2015 BMW X1 Review In Austria: Coming To Malaysia Q4 This Year