100 Years Of BMW: How BMW Wrote The Greatest Comeback Story Ever

汽车专题With products ranging from the science fiction-like BMW i8 plug-in hybrid to iconic MINIs to incomparable Rolls-Royce, it’s hard to imagine that just 60 years ago – an era that your parents might remember - BMW was perceived to be inferior to Alfa Romeo, Volvo, and even Ford. Some even thought that BMW stood for British Motor Works.

World War 2 reduced BMW to a maker of pots and pans, and If not for a last minute rescue plan by a Daimler shareholder who secretly admired BMW, BMW might now be just a parts supplier to Mercedes-Benz.

The story of BMW’s comeback is one of the greatest comeback stories in the industry.

‘The Ultimate Driving Machine’ is the world’s most recognised tagline. BMW’s strategy of segmenting products along the ‘Series’ name set the template that is followed by nearly every premium brand. The practice of using a high performance halo model (M Series) in the marketing of regular models, is now aped by Mercedes-Benz’s AMG, Audi’s RS, and Lexus’s F range of models.

This is a story of how of the power of youth, discipline and respect for people can push a tiny, almost bankrupt company to overtake its seeming indomitable foe - Mercedes-Benz.

Origins

BMW’s origins can be traced back to 1916, as a maker of aircraft engines.

Karl Rapp’s company Rapp Motorenwerke manufactures aircraft engines for Gustav Otto’s aircraft company Otto Flugmaschinenfabrik. The two would soon run into financial difficulties after World War 1.

In 1916, under the stewardship of financier Camillo Castiglioni, Rapp Motorenwerke was renamed into Bayerische Motoren Werke (BMW, Bavarian Motor Company), but this BMW was not the same BMW that we know today.

From here onwards, the narration of BMW’s history gets a bit complicated.

Gustav Otto is the son of Nikolaus Otto, the inventor of the four-stroke engine used by nearly all cars today. Struggling with poor business, Gustav’s company was later renamed to Otto Werke and later on 7-March 1916, reorganised as Bayerische Flugzeug-Werke (BFW, Bavarian Aircraft Company), the predecessor to the present day BMW.

In 1919, Germany had lost World War I, and was barred by the Treaty of Versailles from manufacturing war planes. This severely affected BMW (Rapp) and BFW’s fortunes.

BMW, the one from Rapp Motorenwerke, had to resort to manufacturing braking systems for trains under license from Knorr-Bremse. In 1920, Castiglioni sold BMW to Knorr-Bremse, effectively making BMW a subsidiary of Knorr-Bremse, thus ending the lineage of the so-called ‘original’ BMW company.

In 1922, Castiglioni had assumed control of Gustav Otto’s BFW, and at the same time, Knorr-Bremse had little interest in engine manufacturing and sold the rights to the BMW name back to Castiglioni, who also took a small group of BMW employees with him.

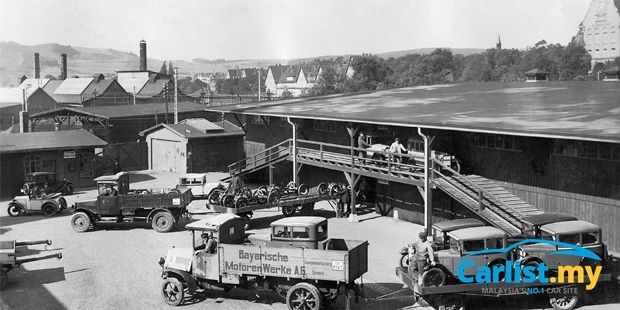

Castiglioni wasted no time to reorganise BFW into BMW. BMW’s engine manufacturing business was restarted at BFW’s former production facility at the Oberwiesenfeld airfield in Munich, where BMW’s Munich plant and Group Headquarters office remains until today.

Thus, after this complicated genealogy, 7-March 1916, the date of Bayerische Flugzeug-Werke’s founding, was considered by BMW to be its date of birth.

The BMW Logo – Aircraft propeller or Bavarian Flag?

There is a prevailing myth that BMW’s blue-white roundel logo is related to BMW’s history with aircraft, but this only a myth, as explained by a BMW archivist in the video below:

From Planes To Cars

Unable to make planes, BMW started building cars and motorcycles. The 1923 BMW R 32 was BMW’s first motorcycle.

In 1928, BMW acquired an automobile production plant in Eisenach from struggling car maker Automobilwerk Eisenach, which had been licensed to produce Britain’s Austin Seven under the Dixi DA-1 3/15 name.

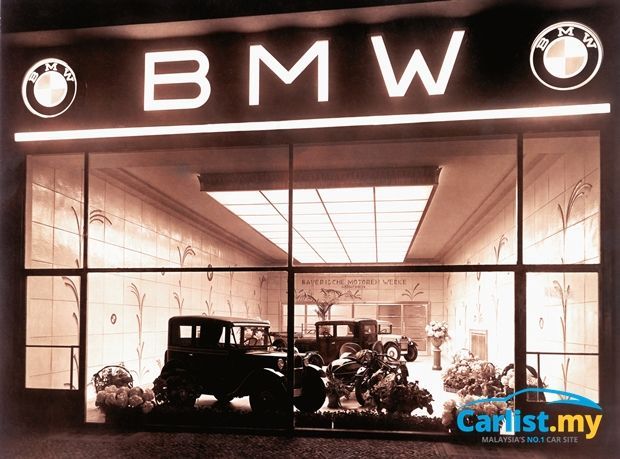

BMW continued producing the Dixi, technically BMW’s first car, until 1932, after which BMW had gained sufficient know-how to build its own cars.

Just four years after acquiring the Eisenach plant, BMW engineers were able to build a more powerful engine, and fit it into a larger BMW 3/20 – the first car to wear a BMW badge. It produced 5 hp more than the Austin-based Dixi, and was built on a BMW’s own chassis, which had a longer wheelbase.

BMW continued to gain momentum and each subsequent model was better than before. The brand quickly became synonymous with superior handling and performance.

The signature ‘kidney grille’ and six-cylinder engine made its debut in the 1933 BMW 303.

The BMW 328 was the peak of BMW’s reputation until World War 2 nearly destroyed everything BMW had.

On 14-June 1936, at the International Eifel Race in Nurburgring, the 328 made its first public debut. Despite having a lower power output 2.0-litre six-cylinder engine, it beat several more powerful supercharged rivals to win the race and set a new lap record for sports cars, firmly cementing BMW’s image for superior handling prowess.

Destroyed By Bombs, Nearly Got Sold To Mercedes-Benz

World War 2 hit BMW particularly hard, harder than either Audi (Auto Union), Mercedes-Benz, Porsche or Volkswagen.

Unlike its more established German peers, BMW had only one car plant – the Eisenach plant, which had fallen into Soviet Union’s control.

The Munich engine plant was heavily bombed, and whatever machinery that was spared from damage was dismantled by US military and shipped out of Germany. What was left was only good enough to make bicycles, pots and pans.

Germany was soon split into two by the Berlin Wall and there was no way for BMW to recover its automotive assets from Eisenach.

In 1948, the company was somehow able to produce a new motorcycle at its Munich plant – the R 24. For seven years after the war, the company that conquered the Nurburgring did not build a single car.

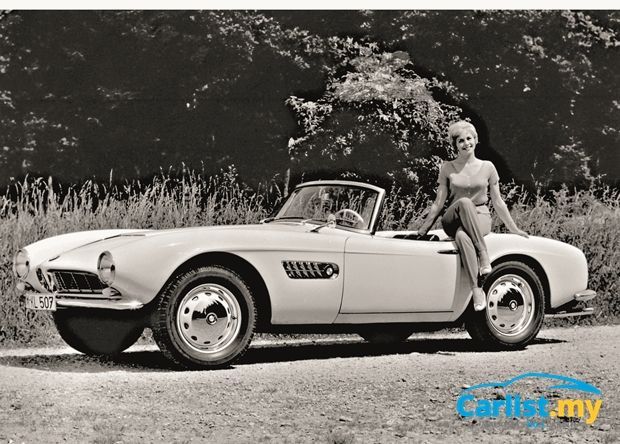

The 1952 BMW 501 (above) was BMW’s first post-war car, followed by the 507 roadster (below), but post-war Germany had little appetite for six-cylinder saloons and sports cars.

The 1955 BMW Isetta ‘bubble car,’ an improved version of a design purchased from Italian carmaker Iso, was a last ditch radical solution to keep BMW afloat but it couldn’t stave off the looming bankruptcy.

By 1959, Daimler, which owns Mercedes-Benz was circling over BMW like a predator waiting for a weak prey to collapse. If BMW falls under Daimler’s control, BMW would almost certainly be reduced to nothing more than an insignificant part of Daimler, probably a parts supplier.

BMW’s shareholders, while acknowledging that there was no way for BMW to remain independent, their Bavarian pride couldn’t stomach a sale to Daimler and protested. The rivalry between Daimler and BMW goes beyond just business. There is a quirky German cultural dimension to it as well.

BMW hails from Munich, Bavaria while Daimler is from Stuttgart, Baden-Württemberg, a Swabian region. The Bavarians are very proud of their identity and see themselves as a distinctly different from their Swabian counterparts.

BMW shares were owned by many Bavarian families, who don’t sell it but passed it down to their children.

For many BMW shareholders, selling BMW, the pride of Bavaria, to the Swabians at Daimler was a major slap to their Bavarian pride.

A Daimler Board Member and Closet BMW Fan To The Rescue

In came Herbert Quandt, the first protagonist in the unfolding drama of BMW’s rescue. Herbert was a wealthy industrialist whose family owns battery company Varta. He owned many shares in the then Daimler-Benz AG and sits on Daimler’s supervisory board.

Curiously, despite his position at Daimler, there was something about BMW that attracted him. Herbert changed his mind about supporting Daimler’s position at the last minute, after witnessing the strong pride among BMW employees and shareholders, and their relentless effort to keep Daimler out of BMW. Some also say that Herbert, a car lover of sorts, did not want to see BMW gone after being attracted to BMW’s sportier, more emotional cars.

Against his financial advisor’s advice, Herbert poured a lot of his own money into the ailing BMW, snapping up much of BMW’s shares and made arrangements to put together an emergency fund for BMW to stave off bankruptcy. Quandt bought 30 percent of BMW’s shares just to that Diamler-Benz would not be able to buy it. He even negotiated with the Bavarian Financial Ministry for assistance to keep BMW independent.

As he was taking a huge risk with his personal wealth, he needed to be absolutely sure of BMW’s potential. BMW’s engineers had already developed a prototype BMW 700, a rear-engined small car powered by a flat-twin 697cc motorcycle engine.

David Kiley’s book ‘Driven: Inside BMW, the Most Admired Car Company in the World” tells of the then Head of Finance at BMW, Ernst Kampfer driving the prototype BMW 700 to Herbert, who then ran his hands over the car’s design (Herbert suffered from failing eyesight, and needed an assistant to read documents to him), and inspected the car’s interior by hand.

Using his position in Daimler, Herbert had Kemfer drove the car to Stuttgart to have the car inspected by Daimler engineer Fritz Nallinger. Fritz drove the prototype BMW around Daimler’s test track, and told Herbert that apart from the dangerous location of its fuel tank (in front of the car) and its weak motorcycle engine, it was a fine car.

“Yes, build it!,” Fritz told Herbert.

It was a commercial successs, and stabilised BMW's finances.

After confirming that he had a decently good product, Herbert used his business contacts to hire talented engineers away from Borgward Works, another struggling German carmaker.

Herbert now had the car and the engineers. He needed someone to sell the car. For that, Herbert recruited two more individuals, Bob Lutz and Eberhard von Kuenheim.

The next part will explain how these two individuals came together put in motion the plans to execute one of the best marketing moves in history, and turned the ailing company to be become one of the most admired companies in the world. Click to read Part 2 of the story.

Find your dream BMW here on Carlist.my.